From the Poland Files: He Did It for La Patrie

After work one day, we went to Mózg, the town art bar. Mózg means Brain, or A Brain, or even The Brain. It was spacious and comfortably pretentious: black velvet curtains hung on the walls, grotty sofas, beer-stained canvases for sale. The clientele were mainly young men with ponytails and glasses who wanted to discuss politics, and lovely girls who didn’t. At Mózg you could buy 40 kinds of vodka, and two kinds of beer—both of which went down like razors. Behind a mesh of chickenwire, there was a girl drilling the anti-theft devices out of cassettes and selling them.

Steve got in the first round of beers. We English teachers shuffled to our corner sofa and got down to another night of ETT (English Teacher Talk, or shop talk. The acronym was based on the pedagogical concept of TTT—Teacher Talking Time. Both TTT and ETT were supposed to be minimized to create nurturing space for the emergence of a real conversation.)

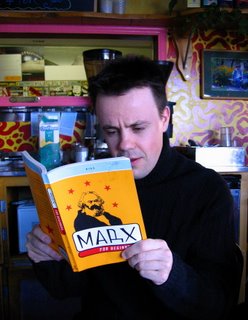

Kieran complained about his students. Sarah complained about her students. Steve, fiddling with his earring, complained about his students. I started to tell them about a great book I was reading, interrupting myself to complain about my students. Everyone drank furiously—this was going to be a long night.

Thankfully, Will arrived, plunked himself down and told us about the time he used to be a parking valet in London and had had to drive an arch-criminal’s Harley the wrong way through the Dartford Tunnel to get it to an armored parking garage on time. He bobbed, he weaved, he ducked mirrors. Later he got a phial of poppers as a tip. We nodded appreciatively as he drained his glass. Will and his shoulder-length red hair were twenty years older than the rest of us. None of us had any real idea where they’d come from. One of the new teachers, too clever by half, began asking questions trying to pick holes in the story, but we shut him up quick. It was a great story, and we were glad to hear it. Will’s pasts were replete with sex, drugs, violence and John Bull outdrinking and overcoming all feeble gestures towards modernity. Like cartoons, there was no problem of guilt or neurosis. The dead were reassembled off-screen to turn up again with such energy that there was no time to ask questions. All there was to do in this town was drink or go to one of the two one-screen theatres to soak yourself in Hollywood’s more bankable reels. You took diversion where you could get it.

It was shaping up to be an unremarkable night, when a very large Polish man in jeans and a sweatshirt approached us. He had the #2 shaved head, jutting chin and heavy build that you only see on Polish men or professional boxers. He asked whether he might be permitted to sit down. We said sure. He sat down. He looked at us in turn. I tried to guess whether I came up to his shoulder. In a steady voice he said something in Polish that we didn’t understand. We swallowed hard. Then he said in good French:

“I overheard you speaking. Forgive my rudeness. I always enjoy speaking with foreigners because it’s the only real talk you get around here.” I got over my surprise to translate this for my friends. We were all surprised: English, German, Russian, maybe, but you just didn’t meet locals here who spoke French. His name was Grzegorz. He was indeed a local. Before Solidarity and the fall of communism he’d vamoosed to join up with the French Foreign Legion in North Africa. Those were his brothers, his real family. Those were men who acted like men. Once you’ve lived in the desert with men and drunk under the desert moon and fried and eaten snakes together and practiced garroting each other, you’re brothers.

Following our approach with Will, we egged him on and asked him all kinds of fool questions about secret missions and death and glory. He clammed up and half turned away, telling us that he knew we thought he was a dog. No, we told him, you’re no dog. Tell us more about Tunisia. No, he said, it’s no use, to you I’ll always be a dog, a dirty dog. Not at all, we said, winking to each other, how can we show you you could never be a low-down dirty dog to us?

He said we could look at his tattoos, that would help. A couple of us demurred. But by now we were high on our own hilarity and really kinda curious so we said, OK, show us. He lifted his sweatshirt, turned away to reveal the kidney area of one side of his back. The swastika was black, turned 45º, about six inches across, scored into him with a blunt needle unlikely to have been held by any very sober hand. Kieran groaned. Sarah clapped a hand to her mouth. Grzegorz rolled up his sleeve to show us more. He had some cryptograms jotted across his bicep.

“I know you think I’m a racist dog,” he said. “But this says death to Jews and Muslims. We all got this one when we were initiated.” Well of course he did. Will tried to change the subject by asking about the fate of a bar he used to bounce at in Tunisia. The rest of us tried out cowardly excuses to ready ourselves for a cowardly back door sneak-out. When Grzegorz saw how antsy we were, he told us he hadn’t meant to offend us, and he was taking us all out for a steak dinner. We pointed out that it was past midnight and Polish restaurants close at eight. Besides, even though we were English teachers trained to live on beer, some of us had actually had dinner.

“You will come with me,” he said, in the same toneless French. “Taxis for everyone. I’m buying you all steak dinners.”

“Nowhere to go. Next time.”

“I know a woman in the country who’ll cook us all steak dinners.”

Yes, his plan was to tumble his poor aunt or sister-in-law out of bed, tie on her apron and make her cook for ten. Jesus. Did he really think she had a decade of fresh steaks and trimmings in the fridge? What did he really want with us? Just what bad habits had he picked up during those long Tunisian nights, staring up into the mad face of Orion? Was I going to be just another statistic—the latest English teacher turned gimp? Would we be pressed into his local chapter of the Legion and marched across the desert to garrote Semites indiscriminately? We were cowards. We knew this had ceased to be a time for politeness, but we went on declining as politely as we could. He would have none of it, we were leaving in five minutes for steak dinners. He got up to piss. We scrambled for the door and clattered down the stairs and through the alley to the silent street. The icy air burnt our lungs. Not far away we poured ourselves into taxis whose moustachioed, Sobieski-smoking drivers whisked us home.

The next day we could not agree whether from the street a voice had been heard booming out “I am not a dog! I am not a dog!” But sometimes since, bored with those who pass for lunatics these days, I like to think that I did hear it.